Awkward Beauties

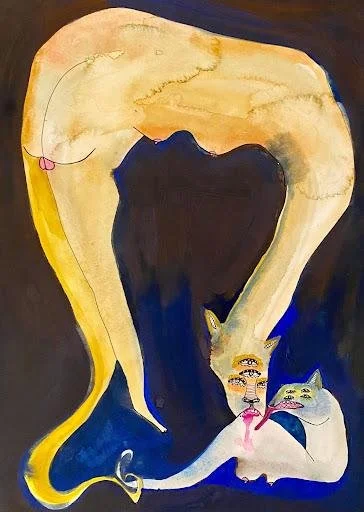

Jessie Mott We Hold Your Gaze, 2021, gouache, water colour, ink, acrylic, marker on paper, 30” x 22”

Essay Written by Jessie Krahn (Editor, The Manitoban, UMIH Graduate Fellowship Recipient 2022-2023)

My favourite things are weird, strange, and beautifully awkward.

In October 2022, UMIH collaborated with Mentoring Artists for Women’s Art (MAWA) to host an exhibition entitled WE HOLD YOUR GAZE_Remix. WE HOLD YOUR GAZE was beyond quirky in form and content, pairing variegated, sparkly paintings with scrolls of poetry. The exhibition is the collaborative creation of Like Queer Animals (LQA), a duo comprising Chicago-based artist Jessie Mott and French-Québécoise queer scholar Chantal Nadeau. Mott creates the illustrations—all anthropomorphic hybrid creatures—while Nadeau writes the poetry for the accompanying scrolls.

The creatures are perplexing, indecipherable, and a little mischievous. Conjoined, hoofed giraffe-like entities with leopard torsos and purple heads haughtily turn away from each other; salacious pink and verdant green snakes coil together; a humanoid cat presents its hindquarters while a cat-snake rolls around beneath them. None of the creatures can be described using the names of single species, adjectives, or bodies. They are each at once one thing (hybrids) and many things (often combined with deer).

Nadeau’s poetry, staged beside the creatures, almost ventriloquizes them. One poem, stationed just above a neon-pink-phallused, golden-mustachioed unicorn goat, reads:

every time

you pretend

to see us

under the rule

of your law

we

hold

your

gaze

“The creatures’ weirdness permits

(or perhaps demands) colourful critical writing of complimentary quirkiness.”

This poem, which I like to think as one of the exhibition’s defining pieces of literature, points to the fraught ethical ground from which we, the visitors, observe. Any attempt to corral this fantastical zoo would be to impose an outside ruleset onto the creatures. Rather than drain them of their agency, though, our gaze is held by the creatures. We are transfixed, they transfix.

Part of my attachment to this exhibition does stem from how much fun it is to write about. In an article I wrote for The Manitoban, I described one piece as “a multi-breasted fox- deer almost twerking energetically as zig-zags emanate from its rear into the background” and another as “a cat or deer-like creature reclining against a dreamy blue and gold backdrop with glittery pink wings reaching towards the edge of the frame.” The creatures’ weirdness permits (or perhaps demands) colourful critical writing of complimentary quirkiness. How often can a writer pun that a piece is “cheeky” (as I got to) by referring to both butts and wit in the same breath?

Mott and Nadeau are inspired by medieval bestiaries, texts which of course come with their own antiquations and therefore limitations. Those limitations are (surprisingly) more generative than inhibitive. Nadeau explained at the exhibition’s launch that refashioning medieval bestiaries works to “invite audiences to reimagine how we see, feel, hear, touch and are touched by non-normative bodies,” adding that the artists refer to this as creating “a queer bestiary of emotions.” In remixing something old, the pair could envision and precipitate evolution into something new.

Installation view Like Queer Animals: We Hold Your Gaze At Mentoring Artists for Women’s Art Winnipeg (MAWA)

LQA has also experimented with superimposing the creatures on images of locations that hold some political or emotional import. Because the pair identify with the creatures, the creatures communicate certain emotions that are otherwise difficult to articulate. One of the most striking examples is an image with a gargantuan, kaiju-like creature photoshopped behind the site where the Black Panthers’ Fred Hampton was assassinated. In this way, deeply personalized representations stand in public settings to dissolve the flimsy and porous membrane between the personal and the public.

What’s most compelling to me about Mott and Nadeau’s work is the way these awkwardly beautiful creatures embody productive political contradictions. This may sound odd. What exactly is so political about a thicc hybrid deer thing? It’s that the animals are so queer!

Resisting Queerbaiting

In popular culture, there is a frustrating strain of discourse which seems to resurge sporadically depending on how recently a touring pop star wore a sparkly outfit. Internet users have taken to accusing public figures of “queerbaiting,” a term which usually applies to media that coyly queer-codes its characters without canonizing queer relationships in its plot. Keen-eyed readers will notice the term is usually applied to fictional people, not real ones. The term’s definition has been warped as internet users deploy it to criticize celebrity figures like Harry Styles and Billie Eilish. These pop stars’ outfits are usually cited as evidence of their queerbaiting.

What seems to be energizing these discussions is partly some fandoms’ directionless investment in social justice combined with an informal introduction to queer politics. Many of us are not learning about queerness through intimate connection to queer communities nor under the structured and careful guidance of an expert in a scholastic setting. In our current atomized arrangements, we are often first exposed to ethical debates, queer codices and queer theory through memes on social media.

Behind the scenes footage of music video for Watermelon Sugar sourced from Harry Styles on YouTube

This is good on one hand, because information is not as siloed as it might be without ample bandwidth. On the other, the architecture of social media platforms is designed to drive engagement, not learning, and so the mimetic versions of complicated stories which do permeate mainstream discussions are often reductive and inflammatory. An internet user who knows absolutely nothing about queer theory is far more likely to click on a post which introduces the subject in an outrage-bait soundbyte format than a carefully-worded explanation. So people come to know about queer culture and the ethics of queer representation through an angry, snarled grapevine which leaves them poorly equipped to apply newfound knowledge or channel fresh rage about cisnormative society.

It’s interesting to me that LQA’s creatures float in indistinct, smoky ethers. The illustrations’ backgrounds evoke the locationless everywhereness of internet communities: the twerking cat-deer I saw was both in Winnipeg and elsewhere at the same time, wherever its background was really set. Isn’t this what it feels like to be online, to chat with a stranger who may or may not even be in the same country as you and to whom you present the same startling omnipresence or nowhereness? I digress.

The problems with accusing a real person of “queerbaiting” with their appearance, comportment, mannerisms, or any other form of self-expression, could run an infinitely long list. For one thing, the accusation not only coerces people to disclose their sexualities, it moralizes not coming out. Some people might not be ready to disclose, and so being forced to come out makes them visible targets of hostility or violence. The expectation that anyone needs to publicly justify their visible queerness by coming out removes agency from the subject and suggests people’s right to privacy is overridden when an onlooker merely feels uncertain about them. What happens in these situations is that the people who do not come out when fans demand it become subject to growing scrutiny and suspicion. Surely, if you were not queerbaiting, you’d have nothing to hide, right?

“The expectation that anyone needs to publicly justify their visible queerness by coming out removes agency from the subject and suggests people’s right to privacy is overridden when an onlooker merely feels uncertain about them.”

LQA’s creatures stand in stark defiance of these sorts of demands to make queerness intelligible. It’s not that the animals are or aren’t queerbaiting that is so arresting about them. It’s that for the viewer to apply the label of “queer” to them is a way of accepting our own uncertainty. Rather than attempt “to pretend to see” the creatures under our own jurisdiction, “the rule of [our] law,” we have no choice but to accept their unintelligibility. Any individual who “queerbaits” is, as such, impossible to see as anything but a wacky hybrid creature who holds the gaze of an audience which attempts to impose its rules on others. The creatures present a possibility for restoring agency to the queer person or “queerbaiting” person compelled to bring clarity, certainty, and easy distinctions back to an observer.

But Harry Styles and Billie Eilish are obscenely wealthy and, psychological distress aside, they can afford supports for coping along with platforms for speaking back to their critics. I’m more disturbed by the message this queerphobic digital heckling sends to queer folks looking on. Demands for celebrities to disclose send a message to queer fans that there are right ways and wrong ways to present as queer. So, regardless whether your self-representation is one which feels most authentic to you or not, these criticisms communicate there is a possibility you are doing it wrong. You’re not being yourself by wearing a dress, you’re mis-stepping.

Details of artwork by Jessie Mott (left to write): The Lovers II, 2021, gouache, water colour, ink, acrylic, marker on paper, 16” x 12”; Red Panther, 2021, gouache, water colour, ink, acrylic, marker on paper, 16” x 12” ; Trouée, 2020, gouache, water colour, ink, acrylic, marker on paper, 24” x 18” ; Le Feu au Cal II, 2021, gouache, water colour, ink, acrylic, marker on paper, 16” x 12”; Le Feu au Cul III, 2021, gouache, water colour, ink, acrylic, marker on paper 16” x 12”

Moralizing queer-ish self-representation does not project a healthy queer ecosystem. What these conversations accomplish is reinforce the notion that queer people are not allowed to experiment with self-expression unless they have the privilege of being already claimed by, or publicly identifying with, the queer community. The implication is that self-representation is appropriation unless the audience feels certain they can place the subject’s sexuality or gender. Your unauthorized authentic self is twisted into a moral failing because other people don’t feel like they know enough about you.

This noxious concoction of moralistic surveillance and insistence on stereotypical legibility ultimately speaks to, and exacerbates, notions of queerness which are highly rigid and extremely limited. I do not think it is a coincidence that this sort of progressively-branded queerphobic moralizing should have cropped up in the period when capitalism seems to be at its most intense. Neither does Nadeau: at the opening of WE HOLD YOUR GAZE, Nadeau cited Roderick Ferguson’s One-Dimensional Queer. Ferguson’s project in this text is to outline the ways queer history has been whitewashed, its intersections with anti-racist, anti-capitalist movements elided, to conform queer politics to mainstream society (3). In other words, the “mainstreaming of gay liberation attempted to turn queerness into an endorsement of state and capital as the satisfiers of queer needs... and as the reasons to make peace with the world that capitalism helped to bring about” (6).

Hybrid component of Dr. Chantal Nadeau’s, University of Illinois at Urbana -Champaign, lecture (live session hosted at Mentoring Artists for Women’s Art Winnipeg). Full video available to watch here

“Gay marriage” has become one such single, emblematic issue to represent the complex and dynamic history of queer politics. Ferguson, too, draws that parallel. “Gay marriage” is framed as such an immense landmark for queer liberation in spite of the institution’s historical connection to the transfer of capital and the way certain legal rights are still withheld from social arrangements that aren’t recognized by the institution of marriage. What gains has “gay marriage” wrought if trans people still don’t have free and safe access to gender-affirming care, if people with uteruses and disabled people alike do not have reproductive freedoms? Single-issue politics “provided momentum to the argument that social and political freedom for queers would come through capitalist economic formations” (9).

The idea that “marriage” is synonymous with love is freaky too. Marriage is a specific institution with its own history and a very specific filial connection to legal spheres, whereas the human experience of love is broader and impossible to legislate. “Gay marriage” becoming emblematic of queer people’s enfranchisement into love is indicative of perhaps straight culture’s inability to grasp love outside of the institution of marriage. Lisa Duggan famously labelled this shift in the priorities of queer politics “homonormativity,” or that which “does not contest heteronormative assumptions and institutions” (Ch. 3). Homonormativity repackages queer politics in a language that is intelligible to a “neoliberal public,” in her words.

To return to the example of celebrities “queerbaiting,” I think the scope of these criticisms is largely defined by capitalist axioms: for one thing, an artist’s brand must cohere with mainstream notions of queerness. The image cannot jar with mainstream queerness, it must flow with it. For another, there seems to be a misconception that a certain kind of queer representation in popular media not only facilitates queer liberation, but stands as its equivalent. This isn’t to say that representation doesn’t matter, but it’s to say that stopping at the matter of representation concedes that the current capitalistic media ecology which grips us now is hospitable to queer people. It’s not enough to just have representation in popular media spheres. So long as media production is driven by capital and media ecologies are shaped by capitalist values, media spheres will never entirely align with queer liberation.

One way we might productively critique Styles, Eilish, or any other pop sensation, is in pointing out that they and their teams build a largesse and live a life of splendor and excess but do not redistribute resources to low-income queer communities of colour. Perhaps they also do not do enough to share their platforms with other queer artists of less renown. Ultimately, these critiques are not predicated on the artists’ presentations and are rather centered on their class positions.

GIF from Billie Eillish’s July 2019 interview with PitchFork’s Over/Under series on YouTube: Billie Eilish also rates being a teenager, Avril Lavigne, and more in this episode of Over/Under.

With Ferguson’s thesis in mind, Mott and Nadeau’s work reaches for alternative representations of queerness that are not (yet) sanctioned by capitalist economies. What I like about LQA’s creatures is that they are unmarketable: not that they couldn’t be subsumed into the world of e-commerce, but how would you even consider search engine optimization for products based on these hybrid permutations when they require so much description to even land in the ballpark of communicating what they are?

Listening to Nadeau’s lecture evoked Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s famous Epistemology of the Closet for me. For Sedgwick, we don’t just need to rethink specific notions of sexuality. Our entire schema for approaching the concept of sexuality is flawed. Mainstream notions of queerness especially are defined using the binaristic tools of a cisheteronormative episteme. That is, those notions accept flawed queerphobic premises which mainstream notions of queerness are built upon, therefore affording a “conceptual privilege” to the heterosocial (31). Sedgwick points out that sexuality is much more than just the gender of who we’re attracted to (35), it’s a matter of how old we are, if we orgasm or if we don’t, if we use toys, if we have sex at all (35)—these are all very important facets to human sexuality, and yet if someone were to ask us about our sexual orientation, we will very likely only respond with the who part. Sedgwick is troubled by the binaristic “crisis of homo/heterosexual definition” (11) because these definitions preclude an infinite range of possibilities.

The creatures in LQA’s exhibition lean towards these unexplored possibilities, in my view. They are impossible to define using dichotomies, or even trichotomies, as some are hybrids of four or more species and are entangled with another creature. Many of the creatures are mid-action. As such, the creatures not only have history which the viewer does not and cannot know, their poses are not likely permanent ones. Whatever the viewer is able to see in those creatures is not a permanent state. They hold our gaze, but our gaze does not hold them. Because they are so kinetic and perplexing, the creatures parallel a vision of queerness which cannot be reduced to a single issue.

“In other words, our ability to imagine who we can even enter into intimate contact with limits the range of bodies we get close to in the real world. ”

Nadeau’s lecture also reminded me of Sara Ahmed’s Queer Phenomenology, wherein she considers how we come to measure the limits of queerness in the first place. She starts by considering the phrase “sexual orientation”: “to be orientated is also to be turned towards certain objects... if orientation is a matter of how we reside in space, then sexual orientation might also be a matter of residence” (1). Perhaps sexuality is procedural: it may be what arises when we fall in line. As Ahmed says in a lovely little chiasmus, “lines are both created by being followed and are followed by being created” (16). Sexual orientations, then, might be naturalized in a cultural context by iteration and reiteration. We come to think of queerness in terms of marriage, permanence and nuclear families because those are the only paths we’ve been taught to follow. In following those paths, we naturalize them further. The end result is that “the orientations we have toward others shape the contours of space by affecting relations of proximity and distance between bodies” (1-2). In other words, our ability to imagine who we can even enter into intimate contact with limits the range of bodies we get close to in the real world.

LQA’s creatures seem to put these principles to practice and offer up a vision of a queer alternative broken free of the boundaries Ahmed identifies. Their orientations affect the space around them in very physical ways. Some creatures are backgrounded by solid colour, their inner worlds calcifying their outer ones. Others float in multicolored fogs, their environments as uncertain as their moods. What is more, each creature’s “proximity and distance between” other bodies is limitless. I mentioned that some are conjoined or coiled together. Meanwhile, some are in conflict with the creatures they occupy space with, and others exist in solitude. The creatures’ orientations in space are far from monolithic and certainly queer. This is what I appreciate about WE HOLD YOUR GAZE: it doesn’t suggest confining queerness. Rather, the creatures in Mott and Nadeau’s exhibition break out of the borders of their home canvases and occupy the world around them. They absolutely defy and deny easy description and circumscription. They can be two things at once!

Installation Images Like Queer Animals: We Hold Your Gaze exhibited at Mentoring Artists for Women’s Art, Winnipeg

Looking Inward

Single labels, flags, or feelings have never really felt accurate to describe my own sexuality. I’m comfortable with broad labels, like pansexual, or context dependent ones, like demisexual/graysexual. I’ve had conversations with other queer people about why I don’t settle on calling myself bisexual, and truthfully I’m so unattached to any particular term that bi suits me just as well. Some of those conversations have been a little combative; other queer folks have taken issue with whatever term I’ve felt comfortable with on a given day and argued that I ought to use a different term. I think an attitude that holds us back in the fight for liberation from cisheteronormative patriarchy is this inclination to circumscribe queerness, to demand from each other a clear, neat and easy description of what queerness means.

LQA’s work has an element of roleplay or identification. The team’s stories about identifying with creatures reminded me of furries, fans of anthropomorphic creatures. Furries sometimes (though not always) use fursonas or fursuits to explore parts of their identities. The fursona gives people space to breathe, spread their wings, and accentuate new parts of themselves. These identities allow people to inhabit their own contradictions, to be both/and more. A friend of mine decided my fursona was a squirrel. Not only am I a chittering sky rodent to him, I am also a human who identifies with a squirrel, I am literally a squirrel, and I am a human who is not a squirrel. Many of us are shy and slightly ashamed about revealing those parts of ourselves that are nourished by roleplay. Play and fantasy create space for us to explore parts of our identities that would otherwise isolate us in our day-to-day lives.

Carseat Headrest’s eternally relevant question from “It’s Only Sex” resounds: “I don’t care about hundreds of hypothetical people and their hypothetical sex deals, I care about me and my sex deal. What about my problems?” What I hope my fellow young people will think more about is this: weirdness is not automatically worrisome. I accept that I’m only ever going to be awkward, and I might never get a firm grip on what my sex deal is. But therein lies the possibility for furever experimentation.

Works cited

Ahmed, Sara. Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others. Duke UP, 2006.

Duggan, Lisa. The Twilight of Equality?: Neoliberalism, Cultural Politics, and the Attack on Democracy. Beacon Press, 2003.

Ermac, Raffy. “Billie Eilish Claps Back at Those Queerbaiting Claims,” 4 October 2021, Out. https://www .out.com/celebs/2021/10/04/billie-eilish -clap s-back-those -queerba iting- claims

Ferguson, Roderick. One-Dimensional Queer. Polity Press, 2019.

Krahn, Jessie. “Like Queer Animals — a bestiary of anthropomorphic creatures and poetry.”

The Manitoban, 19 October 2022.

https://themanitoban.com/2022/10/anthropomorphic-beasts-poetry-and -where-to-find -

them/43908/.

Lenton, Patrick. “How ‘Queerbaiting’ Became Weaponised Against Real People.” Vice, 4

November 2022, https://www.vice.com/en/article/g5vkny/how-queerbaiting-became-

weaponised -against-real-people

“Like Queer Animals - First Friday Lecture by Chantal Nadeau.” Uploaded by MAWA

Programs. 7 October 2022, https://vimeo.com/758139559.

Sedgwick, Eve. Epistemology of the Closet. University of California Press, 2008.